Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Korchnoi, Andrew Soltis, McFarland & Company, ISBN 9781476671468, 388pp., Hardback $65.00

Grandmaster Andrew Soltis is the author of many chess books, an editor for the New York Post, a columnist for Chess Life magazine, and an eight time champion of the Marshall Chess Club. He lives in New York City. This is his eighth book for McFarland.

Here is how Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Korchnoi is described on the publishers website:

“This book describes the intense rivalry—and collaboration—of the four players who created the golden era when USSR chess players dominated the world. More than 200 annotated games are included, along with personal details—many for the first time in English. Mikhail Tal, the roguish, doomed Latvian who changed the way chess players think about attack and sacrifice; Tigran Petrosian, the brilliant, henpecked Armenian whose wife drove him to become the world’s best player; Boris Spassky, the prodigy who survived near-starvation and later bouts of melancholia to succeed Petrosian—but is best remembered for losing to Bobby Fischer; and ‘Evil’ Viktor Korchnoi, whose mixture of genius and jealousy helped him eventually surpass his three rivals (but fate denied him the title they achieved: world champion).”

The content is divided as follows:

- Preface

- Introduction: The Soviet Team of Rivals

- Four Boys

- Growing Pains

- Overkill

- Culture War

- Spassky, Spassky, Spassky!

- Volshebnik

- Three Directions

- A Takeoff, an Apogee and a Crash

- Why Not Me?

- Private Lives, Public Games

- Candidacy

- Humors

- Whose Risk Is Riskier?

- The Fischer Factor

- Countdown to Calamity

- Epilogue: Four Aging Men

- Appendix A: Chronology, 1929-2016

- Appendix B: Ratings Comparison

- Chapter Notes

- Bibliography

- Index of Opponents

- Index of Openings-Traditional Names

- Index of Openings-ECO Codes

- General Index

There are also thirty photos throughout the book. Subtitled “A Chess Multibiography with 207 Games,” this is biography as story telling. Soltis notes that he wanted to write this book when he was researching Soviet Chess 1917-1991 (McFarland 2000). He writes “everyone who takes chess seriously knows the games of Mikhail Tal, Boris Spassky, Tigran Petrosian and Viktor Korchnoi. But they know very little about their private lives,” and that “some of the most important events in the lives of these four men have been ignored completely by respected sources.” For instance, Korchnoi, at age eleven, “had to use his sled to drag the body of his grandmother more than a mile over icy streets so he could bury her.” And Tal conspired “to have his wife divorce him so that he could play in a major tournament, then drop the divorce proceedings after the tournament.”

Soltis describes the four protagonists as a team of rivals whose “competition helped create a golden age in chess.” He writes, “they fought each other as individuals. But they played alongside one another as teammates.” They studied each other’s games and they influenced each other. He notes their inter-relations were highly complex: “Petrosian and Tal were devoted friends”; while, “the hostility between Korchnoi and Petrosian became legendary.”

Soltis recounts, “Petrosian and Spassky managed to remain good friends even after two world championship matches. When Petrosian won the 1966 match, Spassky joined him at a celebratory meal at an Armenian restaurant and toasted him. Yet Petrosian rooted for Bobby Fischer in the 1972 world championship match because he feared Spassky would become too powerful if he remained with the title. Some of their strained relations can be blamed on what the Russians call ‘sporting malice,’ a way of artificially heightening a player’s intensity. During their 1968 Candidates final match in Kiev, Spassky entered a popular restaurant and noticed Korchnoi at a table, eating borscht. Being Spassky, he greeted Korchnoi and sat down at his table. Korchnoi, being Korchnoi, took his bowl and moved to another table, without a word. He knew that if he was friendly with Spassky he could not play well with him. Petrosian, in contrast, could not play well against someone he truly disliked. Tal seemed to like everyone. But his last wife said, ‘He was a great actor.’”

Another tale told is the following:

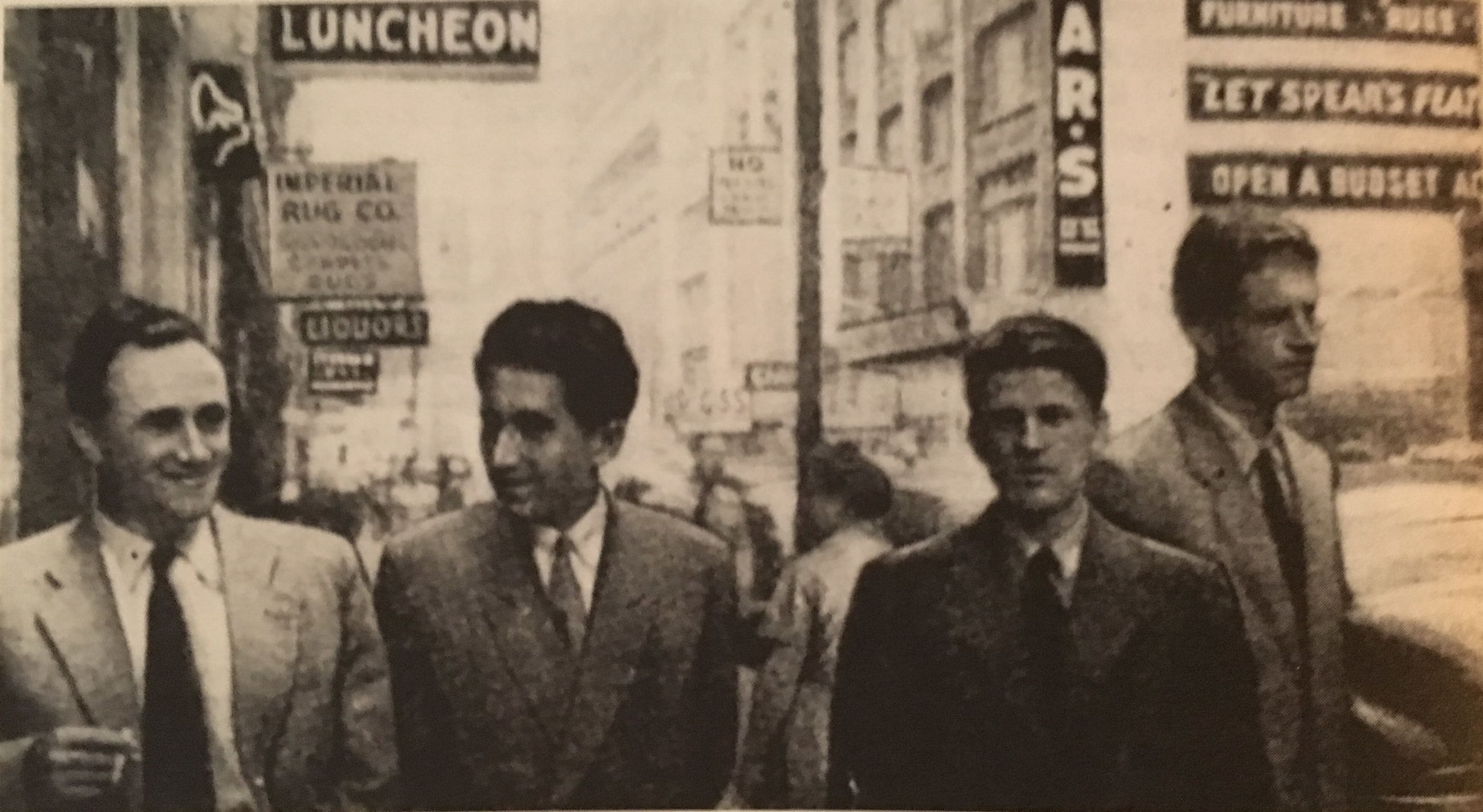

“The biggest prize the Soviets sought in 1954 was victory over the Americans in New York. Chess was so poorly funded in the United States that it did not enter a team in the 1954 Olympiad in Amsterdam. The Soviets scored propaganda points by noting that Colombia, Ireland and even ‘the Saarland’ managed to send teams to Amsterdam but the Americans could not. ‘This fact eloquently testifies to the difficult position of chess organization in the USA,’ wrote Mikhail Udovich.

“A Scandinavian Airlines flight arrived in New York with a large Soviet delegation that included nonplaying captain Igor Bondarevsky, translator Lev Zaitsev, and Dmitry Postinikov, ‘a sort of chaperoning political commissar,’ the New York Times said. The Times added that they were accompanied by Vladimir Ridin and Pavel Smyrnov whose position ‘was not clear.’ This was a hint that they might be agents of the newly formed Committee for State Security, known by its Russian initials, KGB.”

When the players had an opportunity to explore Manhattan on their own, “they passed a toy shop, Petrosian grabbed Zaitsev at the elbow and pulled him inside. ‘There we bought four water pistols and, having returned to [the Soviet diplomatic compound at Glen Cove], began a mad running about, sort of like cowboys, shooting water streams at one another,’ Zaitsev recalled. Petrosian stumbled into the delegation head, the stern Postnikov, ‘and by inertia, spilled water on him.’ That evening they all expected a dressing down but Averbakh, as the eldest, bore the brunt.”

Let’s look at a game:

Josef Kupper – Tal

Zurich, 1959

Sicilian Defense (B96)

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 a6 6.Bg5 e6 7.f4 b5 8.Qf3 Bb7 9.Bd3 Be7 10.0-0-0 Qb6 11.Rhe1 Nbd7 12.Nce2 Nc5 13.Bxf6 Bxf6 14.g4 Na4 15.c3 b4 16.Bc2

[FEN “r3k2r/1b3ppp/pq1ppb2/8/np1NPPP1/2P2Q2/PPB1N2P/2KRR3 b kq – 0 16”]

[FEN “r3k2r/1b3ppp/pq1ppb2/8/np1NPPP1/2P2Q2/PPB1N2P/2KRR3 b kq – 0 16”]

16. … Nxb2!

‘I did not calculate variations,’ Tal claimed after the game. ‘It must be correct.’ That is an exaggeration, of course. But sacrifices like this raised a problem for Soviet annotators. For decades, the proper basis for choosing moves was supposed to be ‘scientific’ analysis based on calculation. This was the method of Jose Capablanca and Mikhail Botvinnik: A sacrifice should be only made as part of a combination in which material was quickly regained or it provided tangible compensation. ‘To sacrifice a piece one should be absolutely sure that one will quickly gain compensation,’ Capablanca had said.

Later in 1959 Botvinnik endorsed this view when the Cuban embassy in Moscow celebrated Fidel Castro’s overthrow of the Batista regime. Botvinnik was among the Soviet celebrities who attended. ‘I especially value Capablanca for his dislike of adventurous play,’ he said at the embassy party. But moves like 16. … Nxb2 could only be termed adventurous. When Tal said he relied on his intuition it ran afoul of Marxist-Leninism. ‘Intuition is the beloved concept of the foreign idealist philosophy,’ as Vasily Panov put it. It was based on the false idea that truth was ‘a revelation from above,’ he wrote.

17.Kxb2 bxc3+ 18.Kxc3 0-0!

Tal needed little more than to see the White king exposed on c3 to decide on 16. … Nxb2. Now 19. g5 Bxd4+ is strong, e.g., 20. Rxd4 Qa5+ 21. Rb4 Rfc8+ 22. Kb3 Rxc2. Or 20. Nxd4 Rac8+ 21. Kd3 e5 22. Nb3 Qb4. Also, 22. Ne2 d5 23. exd5 e4+! 24. Qxe4 Rfe8—although 25. Qxe8+ Rxe8 26. Nd4 is not an easy win.

Pyotr Romanovsky knew what original chess looked like. He had played Capablanca but also Alexander Alekhine. Tal’s games were ‘a new word in chess art,’ Romanovsky said. His sacrifices, ‘for the most part do not have a forcing nature’—as in a combination—but simply ‘create the conditions for attack.’ As Svetozar Gligoric put it, ‘Tal “legalized” the idea of sacrifice.’”

The finish was 19.Rb1 Qa5+ 20.Kd3 Rac8 21.Qf2 Ba8 22.Rb3 e5 23.g5 exd4 24.Nxd4 Bxd4 0-1

Soltis recaps the game with this anecdote: “During his postmortems in the tournament Tal quickly reeled off variations to prove his sacrifices were sound. Other players offered suggestions for the defense. Only Paul Keres was able to refute Tal’s assertions. ‘But my dear friend,’ Keres asked in German after suggesting a move, ‘what is your reply to this?’ Tal answered, in German, ‘Who won?’”

As for the historical records of their individual encounters, Soltis notes that “hundreds of the early—and some later—games of these players have vanished. For example, one authoritative database says that Tigran Petrosian and Viktor Korchnoi played 70 games and the score was five wins for Petrosian and eight for Korchnoi. An equally respected database gives 59 games including 11 victories for each.” Therefore, in selecting games Soltis favored “the lesser-known over the often-published.”

Winner of the Book of the Year Award from the Chess Journalists of America, Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Korchnoi is not just the recitation of dry facts and tournament dates that pervades many other biographies. The stories are humorous, enlightening, and entertaining, and brings forth the humanity of the players. This is the sort of biography I know many readers have been waiting for. Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Korchnoi may be the first McFarland book you actually read cover to cover!

Leave a Reply